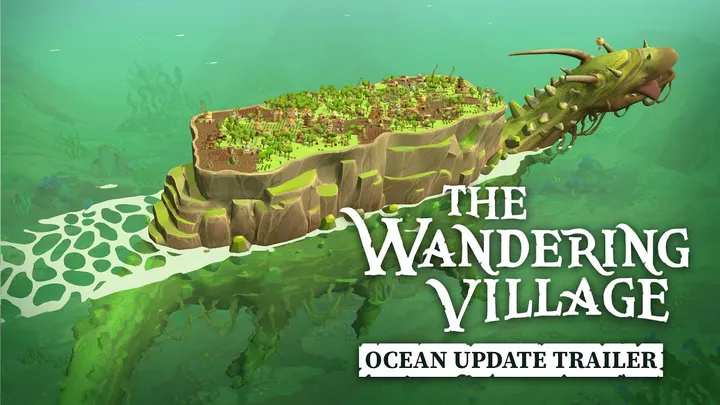

Among all city-building survival games, The Wandering Village stands apart for one unforgettable design choice: your entire civilization lives on the back of a colossal creature known as Onbu. While players often praise the charming visuals and atmospheric pacing, the game hides a far more complex and surprisingly philosophical system beneath its surface. The core of that system—the delicate, evolving trust relationship between humans and a creature they cannot control—is not only the emotional heart of the experience, but also the most mechanically intricate part of The Wandering Village.

This article will dive into that specific issue: the paradox of dependence, where survival requires both symbiosis and exploitation, and where every decision influences Onbu’s behavior, wellbeing, and ultimately the fate of your people. Structured across ten sections that follow the chronological development of the relationship, this deep analysis reveals how The Wandering Village quietly designs one of the most morally layered systems in modern colony-builders.

1. First Contact: The Silent Giant Beneath Your Feet

The game begins without ceremony. Your tribe awakens on the back of a creature they call Onbu—a titan, a mountain, a misunderstood living landscape. This initial moment sets the stage for the emotional conflict that will guide the rest of the experience. Onbu does not communicate, yet everything in the world signals that it is alive. Its steady steps, rhythmic breathing, and rare, subtle reactions create a strange mixture of dependence and alienation.

In these first hours, players often fail to recognize Onbu as an active participant. It feels like terrain—a background system. Yet this is the clever illusion: your entire tutorial is built upon a false comfort, encouraging you to think of Onbu as environment rather than companion. Only later will you learn how dangerous that mindset is.

Early survival is straightforward, but players already experience the consequences of Onbu's movement. Food distribution, climate shifts, and poisonous zones demonstrate that your city is not anchored to the earth. You are a nomad not by choice, but by biology.

The first contact section is about awakening to vulnerability, and the game ensures you understand that you are only a passenger.

2. Early Survival: Learning to Live With the Creature, Not On It

Soon your tribe begins adapting to the wandering ecosystem. Berry harvesting, water collection, and basic shelters all rely on the micro-biome formed across Onbu's back. This introduces the first paradox: your people depend on a creature whose wellbeing they do not yet understand.

During this stage, most players ignore Onbu entirely. The survival pressure pushes players toward optimizing resources and expanding infrastructure. However, subtle cues—like Onbu growing hungry or wandering toward hazardous terrain—hint that neglecting the beast is a dangerous mistake.

This is where the emotional tension begins: the game conditions players to take from Onbu without giving anything in return. You clear trees, harvest stone, and build farms—essentially terraforming a living organism.

Every action tests the boundary between survival and exploitation.

3. The Trust System Emerges: First Signs of Communication

The trust mechanic does not reveal itself immediately. Instead, it seeps into the experience as players unlock new buildings like the Hornblower and Onbu Doctor. These structures represent your first attempt to communicate with or care for the creature. The moment you build them, the game quietly shifts from city-builder to relationship management.

You learn that Onbu responds to commands—but only if trust is high enough. This creates one of the most innovative feedback loops in the genre: your actions directly shape the behavior of a giant creature, but only if you have earned its respect.

Trust becomes a currency more valuable than wood or stone.

Every meal you cook for Onbu, every healing salve you apply, and every harmful action you perform will echo through the rest of the playthrough. This slow reveal shows how the game uses progression to deepen a bond instead of merely expanding technology.

4. Ethical Turning Point: The Temptation to Exploit Onbu

As you advance, the game introduces technologies that cross an ethical line: Onbu blood extractors, spine drills, bile harvesters. These machines offer powerful resources that dramatically boost your civilization’s resilience—but at a cost.

Using them hurts Onbu.

Hurting Onbu reduces trust.

Lower trust means Onbu stops obeying your commands.

Ignoring your commands can lead Onbu into deadly biomes.

Deadly biomes can wipe out your entire tribe.

This is where gameplay intersects moral philosophy.

Players face a critical question:

Will you sacrifice the creature for quick power, or nurture it for long-term survival?

The brilliance lies in the fact that both options are valid. The design does not moralize. Instead, it makes you live with the consequences.

Some players transform into parasitic civilizations. Others become guardians.

Both paths lead to entirely different narratives.

5. The Great Wander: Navigating Poison, Drought, and Changing Biomes

Once you understand Onbu's trust mechanics, the map becomes a shared responsibility rather than a navigational challenge. Biomes shift regularly, each posing different threats: forests affect water gathering, deserts reduce crop viability, poison zones corrupt your entire village.

This is where trust becomes gameplay, not symbolism.

If Onbu trusts you, it will obey commands—allowing you to steer toward safer routes. If trust is broken, the creature wanders freely, often stumbling into death.

The emotional weight of this stage is heavy: your community’s survival depends on the choices of an independent creature… whose decisions depend on your treatment of it.

This loop transforms the entire game from resource-management into cooperative survival. It is an elegant example of how design can reshape a player’s mindset without explicit narration.

6. The Ecology Conflict: Farming the Back of a Living Being

By mid-game, infrastructure expands dramatically. Farms, mycologist stations, composters, and advanced huts create the illusion of stability. But underneath the apparent perfection lies an ecological paradox: these structures are built on the back of an animal whose biology does not match human needs.

Enter the second major issue—resource tension.

Onbu grows tired.

Your farms take up too much space.

Your buildings interfere with its sleep cycle.

Its natural behavior changes because you colonize its body.

Here the game demands introspection. Unlike most colony-builders where land is disposable, here every land tile is flesh. Every new building is a permanent statement of how you view the creature.

This is the stage where players must decide whether coexistence or domination defines their civilization.

7. Crisis Management: Poison Spores and the Fragility of Trust

Poison spore infestations are one of the most dangerous events in the game. They reveal the fragility of your ecosystem and the urgency of maintaining a healthy partnership with Onbu.

Spores spread across the creature’s back, threatening both your tribe and Onbu itself. These crises often expose weaknesses in your city layout, your workforce allocation, and your long-term planning. But the deeper issue is philosophical: the crisis highlights how dependent your people are on the creature’s health.

The player must collaborate with the creature to survive a threat that affects both lives. Onbu becomes neither vehicle nor environment—it becomes family.

This stage solidifies emotional reliance, forcing players to abandon purely exploitative strategies.

8. Late-Game Authority: Mastery, Control, or Harmony

As players reach the higher tiers of the tech tree, Onbu becomes increasingly responsive. Specialized commands allow you to tell it when to sprint, when to eat, when to sleep, or which path to take.

But this mastery is deceptive: it is only granted if trust remains high. If you have damaged Onbu earlier in the game, late-game authority collapses. You lose the ability to influence crucial decisions, and catastrophic events spiral.

What emerges is a form of indirect leadership. You cannot control Onbu—you can only guide it. The creature must want to follow you.

This mirrors real ecological relationships, where influence arises from respect and care rather than domination. Few games capture this nuance so effectively.

9. The Ethical Endgame: Will Onbu Live or Die?

In the final stretch, everything converges. Your earlier decisions determine whether Onbu thrives, struggles, or collapses. If you have exploited it for resources, it may ignore commands, starve, or wander into toxic wastelands. If you have cared for it consistently, it becomes a fully cooperative companion that actively protects your people.

This creates one of the most unforgettable emotional climaxes in the colony-building genre:

the creature you built your life upon either survives because of you, or dies because of you.

The ending is not cinematic. It is experiential. The story is told through mechanics, not cutscenes. The fate of the giant becomes a reflection of your leadership, morality, and empathy.

10. Legacy and Reflection: What The Wandering Village Teaches Us

Once your run concludes—whether victorious or tragic—the game leaves you with a haunting sense of reflection. The mechanics have taught a lesson without preaching: survival is intertwined, and exploitation has lasting consequences.

Onbu is not just a creature. It is a metaphor for the environment, for ecosystems, for the world we inhabit. Your tribe represents humanity’s ambitions, and the trust system reflects the fragile balance between progress and sustainability.

In this final stage, players understand that The Wandering Village is not a story about building a city. It is a story about building a relationship.

Conclusion

The Wandering Village stands out not because of its visuals or its charm, but because it integrates morality directly into gameplay. Its trust system between the tribe and Onbu forms a rare ecological narrative where every decision shapes the fate of two species entwined by survival. By exploring this singular issue—the paradox of nurturing and exploiting the same creature—we see how the developers created a city-builder filled with emotional weight, environmental metaphor, and philosophical depth.

This is not a game about managing a village. It is a game about learning how to coexist.